THE LATEST | CAMPUS EVENTS | NEWS | COMMENTARY | BEST OF WFTU

The backstory of how a 44-year old concept found a home at Five Towns College.

Illustration: Janell George

By Gillani Peets

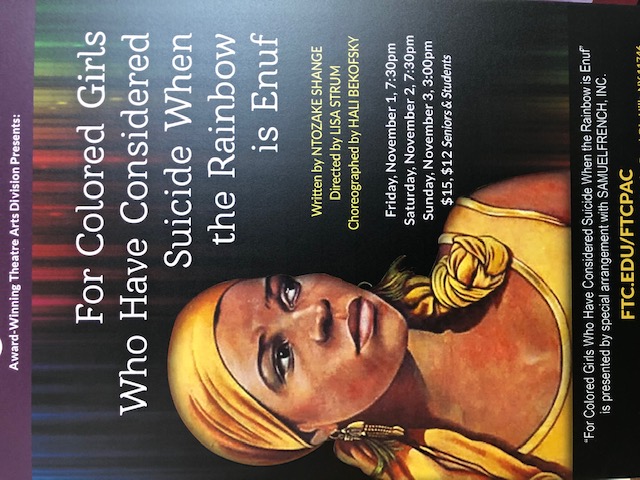

On the Night of November 1st, 2019, a crowd assembled in unison to witness a testimonial performance spotlighting eight African-American women. A first of its kind for Five Towns College, the venue in which the performance took place, the college welcomed alumni, family, professors, students, scholars, and paying theatregoers to a once-in-a-lifetime event. Some entered the building that cool autumn night, wondering how eight students could revive a beloved 1970’s classic for an audience unfamiliar with the material or the historical background regarding said performance. Others entered reassured, without seeing a preview or video advertisement, that they would be a spectator to a thrilling production.

As guests headed to their seats, prominent black vocalists filled the air. From Anita Baker’s passionate romantic enchantment in “Sweet Love” to Aretha Franklin’s demands for visibility in “Respect.” From TLC’s acknowledgment of self-worth in “No Scrubs” to Lauryn Hill’s ageless message of sexuality in “Doo Wop (That Thing),” the music was a precursor for the audience’s theatrical experience. This performance was created for black women, originated by black women, celebrating black women (through triumphs and tribulations), and undoubtedly, stars BLACK WOMEN.

Backstage, nerves began to foray upon the female-driven cast. A year-long journey of putting forth their state of mind and vulnerability had resulted in a nearly sold-out theatre, anticipating manifestos of being a black woman in a male-dominated atmosphere. As emotions reached a high and as showtime grew closer, the stars and their director collectively prayed, to remember where they’ve been and where they were heading.

“My sisters, I thank you. I appreciate you. I see you. I love you. Ashe,” the cast chanted.

Minutes later, the lights grew dim, the music faded out, and then, the 75-minute performance commenced.

“My sisters are ready!” Mere seconds after the announcement, free-form jazz blared throughout the theatre, a vicious, bold, in your face sound, with each note succeeding the one prior. The female cast ran down the aisle onto the stage and battled forces that withheld their lives through the imagery of rising and falling, embodying the emotional trauma that continuously hovers over black women. Beauty and imperfections. Love and heartache, friends and families. In the first minutes, without dialogue, the performance let the audiences grasp first-hand the unpredictable experiences African-American women encounter daily, the good and the bad.

Minutes later, in finely colored wraps, the eight females projected their hometowns, saying anyone could make it. Theresa Coleman (Lady In Brown, Uniondale); Khenedi Daniels (Lady In Orange, North Carolina); Destini Fell (Lady in Red, Harlem); Shadae Graham (Lady in Pink, Huntington); Laniece Lebron (Lady in Yellow, Hempstead); Tiera Summers (Lady in Blue, Brooklyn); Bria Walton (Lady in Purple, Queens); Kiana Wilson (Lady in Green, Freeport) all proclaimed in unison, “This Is For Colored Girls Who Have Considered Suicide When the Rainbow is Enuf”!

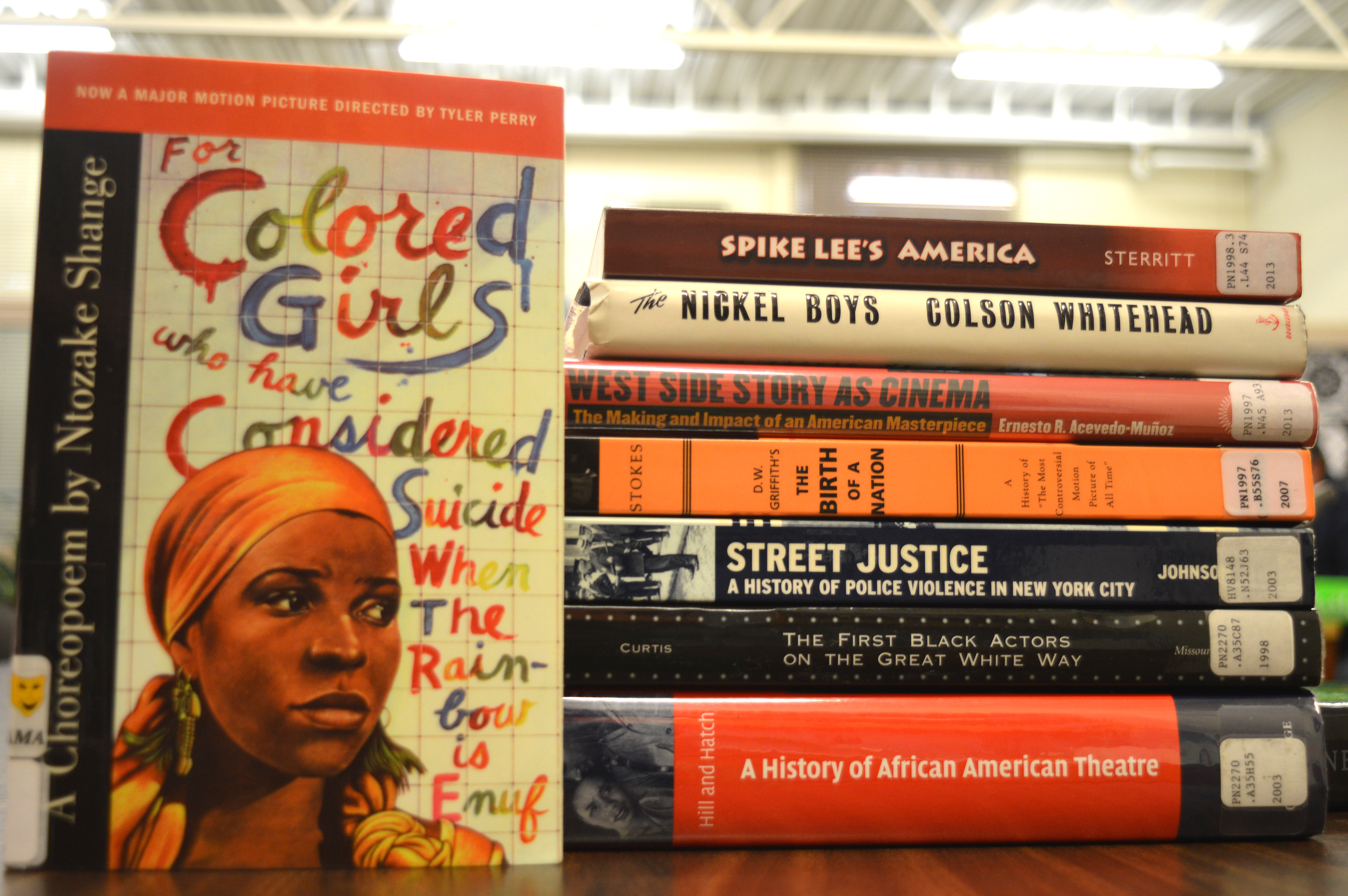

The story, For Colored Girls Who Have Considered Suicide When the Rainbow Enuf, begins with its author, the laureate Ntozake Shange.

Ntozake Shange, born in 1948 under the name Paulette Williams in Trenton, New Jersey, came into a revitalization period for African-Americans.Shange was raised in a six-person household and was the eldest. Sister Ifa Bayeza, would become known for her Edgar award-winning play, “The Ballad of Emmett Till.” Bisa Williams, the youngest, would become known for being an ambassador to the Republic of Niger during the Obama Administration. And their only brother, Paul T. Williams, Jr., was an executive director of the Board of the Dormitory Authority for New York State. Their parents, Paul T. Williams and Eloise Owens Williams, respectively, a surgeon and a professor focused on social justice, moved to St. Louis in 1953, causing a shift in Shange’s environment. A studious child in her youth, Shange came into the mid-south at a time when Brown v. Board of Education strangled the idealistic beliefs for a majority of white southerners. As a result of the court’s ruling, Dewey International Studies Elementary School would be the genesis and early influence on Shange’s writing, where she constantly experienced physical and verbal assaults by classmates based upon the color of her skin.

Five years later, the Williams family returned to New Jersey. Attending Trenton High School, she recalled the experience in The New Yorker with writer Hilton Als in 2010. “I was chastised for writing several obituaries for Malcolm X, exploring different aspects of his writing. One teacher in particular told me, “Didn’t I think I was beating a dead horse?” and dismissively threw my paper on my desk. The others {teachers} just sort of turned away from me in terms of friendship and support.”

After graduating with honors from Barnard College (one of the oldest liberal arts female colleges available to female students), Shange moved to California to complete a master’s degree. Throughout the next several years, she would change her name from Paulette Williams to Zulu figures Ntozake (meaning ‘she who comes with her own things’) and Shange (meaning ‘one who walks like a lion’). Shange earned her master’s degree at the University of Southern California while marrying and annulling from her first husband, and tried multiple suicide attempts stemming from ongoing depression. Taught African-American studies and women’s studies at a variety of colleges in Southern California, she became entranced by a plethora of works by black women such as Nikki Giovanni, Sonia Sanchez, and Toni Morrison, who were all a part of the black female liberation movement where blackness became recognized beyond the shadows.

For Shange, the point when she knew she wanted to express what it meant to be a colored girl in America is when she saw a rainbow while driving along Highway 101, and recognized that she had to live, tell stories, and particularly tell the stories of black women in America. After this moment, For Colored Girls came into fruition as a series of poems connected to seven women, nameless, only defined by their colors.

Performing the poetry at local California bars and cafe, her sister Ife said, “What you have here is theatre, Ntozake.” Reluctant to move out of these spaces, Shange took the poems to New York City under her sister’s advice, and in a year, had a residential spot at The Public Theatre. Performing the poetry alongside six other actresses, Shange would term “choreopoem” to describe what audiences were witnessing. A phrase unbeknownst to many would drum up interest from future Five Towns’ Chair of the Theatre Department, Dr. David Krasner.

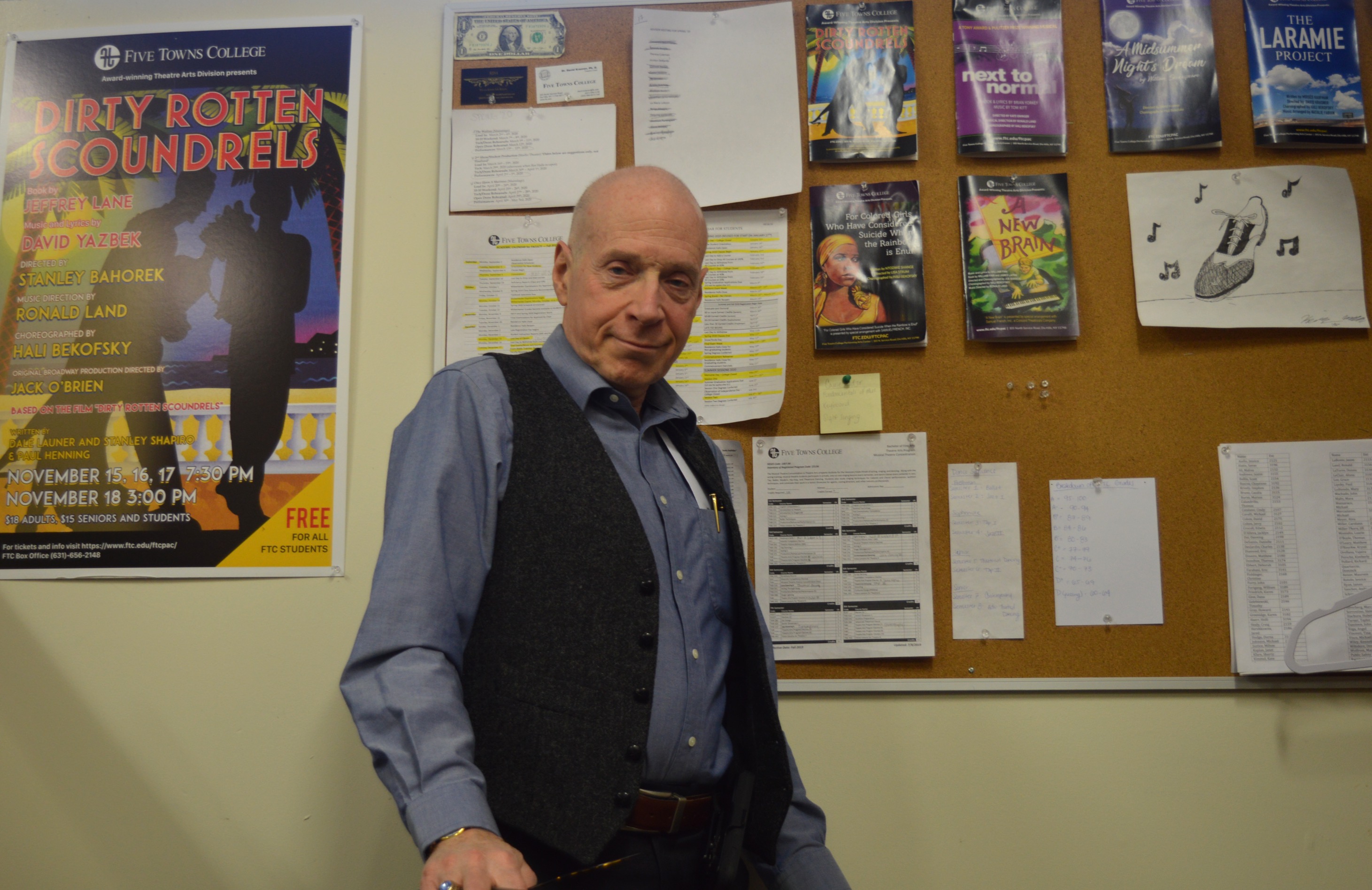

Dr. David Krasner (Photo: Gillani Peets)

While walking the streets of New York City, Krasner ran into an old college friend, Rise Collins. The Carnegie Mellon graduates caught up for missed time, with Collins inserting during their conversation that she was currently in a crafted choreopoem performance. Krasner couldn’t miss the opportunity to witness this innovative, unprecedented concept. A blend of dance, music, and dramatic performance, the term “choreopoem” crafted the very uniqueness that made audiences leap off their television couches for the chance of viewing seven women displaying remarkable, realistic stories of triumph and tribulation. Populating each week during the summer of 1976, Krasner and the theatre world were stunned. In the three months since opening their doors in The Public Theatre, Shange’s Production made its debut on Broadway. Becoming the second African-American woman in history to have a Broadway production, preceded by Lorraine Hansberry’s 1959 Production, A Raisin in The Sun, Ntozake Shange and her cast (Rise Collins, Trazana Beverley, Paula Moss, Janet League, Aku Kadogo, and Laurie Carlos) were nominated for Grammy Awards in the category for Best Spoken Word Recording. Trazana Beverly won a Drama Desk Award and a Tony Award for Best Featured Actress in a Play for her portrayal as Lady in Red; the first of six African-American women to receive this honor. As Jacqueline Trescott eloquently states for The Washington Post, “as it became an electrifying Broadway hit and provoked heated exchanges about the relationship between black men and women…. It’s form – seven women on the stage dramatizing poetry-was a refreshing slap at the traditional, one-two-three-act structures.”

Since witnessing the choreopoem at The Public Theatre, and again at The Booth Theatre, Krasner made it an initiative to produce a rendition of the performance someday. A prolific educator, Dr. Krasner has worked as an instructor at The American Academy of Dramatic Arts, directing institutional productions such as Sizwe Banzi Is Dead (a South African play giving an insight of social and political racism black South Africans faced in the 1970s), as well as working as Yale University’s Director of Undergraduate Theatre, Head of Acting at Emerson College, and Dean of the School of the Arts in Dean College. Krasner said, “Out of all of the places I ran, I have never been in a situation where there were at least seven women of color who could do it.”

Coming to Five Towns College in the spring semester of 2018, Krasner was instantly accredited as a champion for giving students equal opportunity. Five Towns College registered their theatre program sometime in 1992, creating a space for actors, set designers, costume designers, technicians, and play writers to accelerate their craft for a world outside the 40-acre campus. Current Five Towns College President, Dr. David Cohen, previously worked as the Provost and Administrator of the college under the guidance of his father, Stanley Cohen, who was the Founder and President of Five Towns until 2014, and still to this day, a profound figure within the college. Under Stanley Cohen, plays and musicals became a revenue source for the college. Avenue Q, American Dating Catastrophe, and The Eddie Money Musical: Two Tickets to Paradise were successful productions that took place when Stanley Cohen was the President and under the guidance of Professor John Blenn, a popular mainstay in the Long Island institution since 2001.

Often wearing jerseys representing local hockey and baseball teams, Professor Blenn joined Five Towns as the playwright resident, responsible for the original comedy and promotion of the plays from 2004-2010. “The first year, we were selling out three of the four musicals. Selling out in advance,” Blenn said.

Reflecting on the commercial focus and appeal of the past productions, Dr. David Cohen said, “It was a different era.” Cohen’s background in higher education and law helped to shape his vision for the theatre department at the college, “We’re not in the ticket sales business, we’re in the educating students business.”

In 2017, when looking for a new head of theatre, the main thought for the President of Five Towns College was “hiring the RIGHT staff.”

“Doctor Krasner brings a different perspective to the curriculum,” Dr. David Cohen said, “We were looking for somebody who had a vision for collegiate theatre programming.” Krasner became first fully involved in Disgraced (a play revolving around Muslim-Americans characters living in post 9/11 world) and has since not looked back on illustrating serious topic matters. But in the back of his mind, the play he saw, nearly 45 years ago, was still an unforeseeable feat.

In the forty-five years since its Off-Broadway debut, For Colored Girls Who Have Considered Suicide When the Rainbow Enuf has had two film remakes with notable performers. The first remake occurred in 1982 on PBS’s anthology series, American Playhouse (A series that remakes Broadway productions for a television audience). The special premiered during Black History Month and ushered in the careers of unknown actresses Lynn Whitfield and Alfre Woodard. Both women are now stars who have transcended in many high-profile projects such as 2018’s Black Panther and 2019’s The Lion King. The PBS Special was met with mixed reception, as The New York Times’ John J. O’ Connor put in his review, “The stage production was almost austerely spare, using music and touches of dance to set the required scenes. The actresses flowed across the stage, sometimes singly, sometimes in groups. There were no men in the production… There are now men on the scene, but they amount to little more than convenient mannequins, striking poses, and very rarely getting a line to speak.”

In summary, the general impact of a television special could be described by the author “as the overall concept devised for television succeeds, more often than not, in diluting the basic material”. The second remake was Tyler Perry’s 2010 film adaptation. Starring an all-star cast of prominent performers such as pop star Janet Jackson, television icon Phylicia Rashad, and Oscar-winner Whoopi Goldberg, the film, even more so than the 1982 film, was met harsh reviews as some, including Oprah Winfrey, expressed doubts about whether a man or the original set of poems could possibly be translated onto film.

While the choreopoem legacy is based on the sheer power and impact of the original Broadway version, each remake had limited influence from Ntozake Shange. So, when Krasner realized he had enough actresses of color to play these titular characters Shange imagined, the process became underway, immediately, with a twist.

“You’re joking. Right?” Tiera Summers asked when Dr. Krasner brought into question her awareness of For Colored Girls Who Have Considered Suicide When the Rainbow Enuf last November. The freshman was only at Five Towns for three months when Krasner told her his plan for the upcoming year. Summers, admittedly, cried.

Unbeknownst to Summers at the time, in Five Towns’ 27-Year Theatre Program, the college had never produced a play focusing on African-Americans. In the last five years, notable diverse stories have been retold, such as Hispanic-Americans living in New York in the college’s rendition of In the Heights, and stories of Muslim-Americans through the Pulitzer-winning Disgraced. However, the majority of Five Towns Theatre productions headed towards well-known musicals titles like Romeo and Juliet in 2016. Producing For Colored Girls for Krasner and Five Towns College, would be a historic achievement. If accomplished.

The ladies that Krasner saw on his roster each possessed a unique story.

Bria Walton, a senior at Five Towns, was the first cast member Krasner told about the production. Walton had been at the college for three years, and in those years, had only been a part of the plays (School House Rock, Playing with Grownups, and Once on the Island) as a supporting character and not in a starring lead. Usually relegated towards ensemble cast or technical crew, Walton said, “After a while, I decided to stop auditioning, because I felt I wasn’t gonna get the part anyways.” When Krasner stopped her to discuss the upcoming production, she remembered saying, “A show for me and my sisters. And we’re all the leads.”

Shadae Graham (Photo: Rashika Williams)

The second person to find out about the production was Shadae Graham. A freshman at the time, Graham rose past the ranks of her classmates as a prolific actress, playing central parts in musicals such as Hairspray, Aida, Front, Annie, Dirty Rotten Scoundrels, and A Midsummer Night’s Dream. Portraying her characters with a sense of humor, Graham became emotional right away when Krasner told her of the production. “With what I dealt with in my old school, from me starting theatre and for me to grow a love and a passion for it, it always felt like it pushed me to the side in that I didn’t have a part of it,” Graham in a panel discussion.

In the same class where Shadae Graham found out, Khenedi Daniels was ecstatic over Krasner’s announcement. At the time a freshman from North Carolina, Daniels had been a part of the productions of Dirty Rotten Scoundrels and A Midsummer Night’s Dream. She exuberantly said in the same group panel, “Yes. Finally, the black girls in the theatre department can finally show them what we’re all about.”

Tiera Summers was the fourth to find out, Laniece Lebron the fifth, and Kiana Wilson, the sixth. Krasner sat with each, ensuring each actress of the show’s stability and undevoted support from the Theatre Department and Five Towns College.

Destini Fell (Photo: Rashika Williams)

The last set of actresses to be told about the production was Theresa Coleman and Destini Fell. Both sophomores at the time; each performer relied on each other since their arrival at Five Towns for support, because in most of their theatre classes, they were the only black females. “People always tried to make us hate each other,” Destini said during the group panel. Theresa later injected an example stating when Destini won a role in Disgraced over her, people said “You should be mad at Destini for getting the role,” but Teresa clapped back saying, “It’s not about who got the role, it’s about seeing an African-American {a sister} on stage.”

Dr. Krasner finally united a group of aspiring actresses to perform a magnitude of a play. And in addition, he announced that For Colored Girls would involve directorial services, but not from him. The cast would be allowed to conduct interviews and select the director of this rendition. “The fact that he wanted to bring in these black female directors for us shows just how much he wanted us to be represented,” said Laniece Lebron.

From December 2018 to January 2019, the actresses interviewed seventeen director candidates, all who affirmed that they wanted to mentor the cast and ring Ntozake Shange’s name throughout Five Towns College. The field narrowed to six people, including three to four African-American female directors. With the assistance of Professor Malisa Ali providing support and guidance for the cast’s constructive critique, the two-month process commenced. The first person the ladies met was a distinguished female with an impeccable repertoire. Her name was Lisa Strum.

An actress in her own right, in addition to being a playwright and producer at the Associate Artistic Theatre Curator of Jersey City Theatre Center, Strum never intended to be a part of the dramatic arts field, originally studying to becoming a trombonist in her teenage years. However, the theatre’s swift effect of telling unflinching stories with actors evoking every detail in their body grasped Strum, instantly taking her away. While living in Seattle over eighteen years ago, she became enamored with For Colored Girls. Having been a part of Seattle’s 5th Avenue production of Hair earlier that year (2002), Strum auditioned for a role in Shange’s play, and to her excitement, won the part of Lady in Yellow. “I just remember feeling that the show was so specifically and clearly for us. For black girls.”

Now, nearly two decades later, the women looked at Lisa Strum, and from the beginning, knew they found their director. “She was strong,” Destini Fell said. “We needed someone like her who could drive us into the text.” Even though the decision wasn’t finalized that day, everyone present in the room knew: Lisa is the first, and the only choice for directing Five Towns’ rendition of For Colored Girls Who Have Considered Suicide When the Rainbow Enuf.

Five months into pre-production, in the Spring of 2019, the concept of the choreopoem was arcane to Five Towns’ student body. How would Five Towns College, a place where musicals and family-friendly productions were prevalent, present a show featuring profoundly sensitive, but realistic material? This was the initial thought when Professor Malisa Ali first heard about the choreopoem coming to the Five Towns. Earlier that year Professor Ali, a sociology professor at the institution since January 2018, helped organize a Disgraced panel for the Theatre Department. Ali herself, a South Asian Woman effected by Americans’ unjust perceptions of Middle Easterners after the September 11th attacks, was greatly moved by the play’s accurate depiction. After viewing the play in October 2018, she said, “Now, I want to see a play revolve around black women” to theatre colleagues, and to her surprise, For Colored Girls was already in process.

Professor Malisa Ali (Photo: Gillani Peets)

Since the beginning of pre-production, Ali took the initiative of planning the production’s revealment ceremony, entitled “Her Story.” “I got the idea when I was doing yoga, and I have the idea of just secrecy,” Ali said. Akin to the promotional posters of the popular teen television series Pretty Little Liars, a photoshoot was set with the cast in late-February 2019 with photographer and Five Towns Mass Communications student, Rashika Williams.

Describing the photoshoot and experience as an honor, Williams took the cast’s pictures draped against a blush pink background. The intent was to complement each actress’ pigmentation, creative sense of style, personality, as well as unique hairstyle. Examples of Williams’ talent and photographic techniques are seen with Bria’s dark mocha skin shining upon her purple highlighted puffs matched with a light-yellow denim jacket and tank top. Theresa’s hair wrapped in a red bonnet, with her twisted blonde braids slithering down. Kiana’s sable skin beaming with a firmly centered afro and matching afro pick, positioned towards the audience’s gaze – all while wearing a striped mustard jumpsuit. And, Shadae’s low-top hair bun complimenting her yellow lace dress filled with adjacent flowers while holding a sunflower, a symbol for happiness and friendship.

“It’s easy because when working with people who are the same race and ethnicity as you, it’s easier to understand the way they want to be portrayed as black women in the world, not just girls,” said Rashika Williams.

Promoted in March throughout Five Towns College, ‘Her Story’ (the title chosen by Professor Ali to represent the plays’ revealment) transpired with another historic event for America. Women’s History Month began in 1995 – but celebrated as Women’s History Week since 1981 – it sought to commemorate the vital roles women have contributed to America’s 400-year history. Ali decided to tie-in the month with ‘Her Story.’

“A lot of times, we hear a lot about white women and women of color end up being a footnote,” said the sociology professor. ‘Her Story’ took place in a packed crowd consisting of more than fifty people in a single classroom and illustrated the stories of female student performers and poets. The cast and Ali came dressed in all-white to commemorate the suffragettes (women who fought to vote in the 20th century). And just as they proclaimed on production’s opening night, in unison each revealed to the packed crowd, “We Are for Colored Girls Who Consider Suicide When the Rainbow is Enuf.”

Photo: Professor John Blenn

After proclaiming their statement on opening night, the cast looked at each other, declaring “Musicccccccc.” First, doing a playful rendition of “Mama’s Little Baby Loves Shortin’,” and then dancing over the sounds of Martha and the Vandella’s “Dancing in the Streets,” audiences are introduced to a set of black women, who are living and enjoying the world around them. Afterward, the first monologue appears, “Graduation Nite,” tackling the magic and blissfulness of losing one’s virginity. Performed by an energic Laniece Lebron as Lady in Yellow, we are introduced to a woman’s inner view towards sexuality. We then transition to “Now I Love Someone More Than,” a poem centering around the joy and love for music. In life, music is an avenue that can explain the pitfalls and victories in under five minutes. Cleverly performed by Theresa Coleman as Lady in Brown, who plays the part to a “T”, capturing the audience through rhythmic dancing every time she mentions her character’s admiration for Willie Colon. Audiences then witness the characters dancing their way into the night. Seconds later, each character plummets with a sickening thud onto the floor, revealing the effects of date rape. “These men are friends of ours, who smile nice, stay employed,” Tiera Summers and Theresa Coleman say in unison.

Theresa Coleman (Photo: Rashika Williams)

Under Lisa Strum’s direction, the cast rehearsed since September, gradually perfecting their craft. Destini Fell explained the endless hours of rehearsals, “Plenty of times we just looked at each other and said, GIRL!!!” Instilling the same wisdom she received throughout her career, Strum taught each actress the true nature of performing arts and knowing your self-worth as a woman of color. For example, Bria Wilson was hesitant to express her desire to include a poem into the show, staying quiet until the last minute. Strum used Bria’s silence as a valuable life lesson, “If you want something, go get it. Speak up. Never hold your tongue”.

In addition to attending their college classes and meeting the demands of friendship and family, throughout the two months of rehearsals, the eight actresses had to immerse themselves in the value of the stage and the production and learn to find their vulnerability. “At times, it was a frustrating process because we really had to break ourselves down to build ourselves back up,” Laniece Lebron said in the group panel.

The group panel took place on October 29th, three days before opening night. Throughout the hour-long conversation conducted by Professor Ali, the actresses were poised and stayed composed, intent on giving Five Towns’ students an insight into rehearsals and the meaning of Ntozake Shange’s historic choreopoem. “The title almost suggests it’s a collection of sob stories, but there is also an amazing amount of celebration of who we are as individuals and a group,” said Kiana Wilson during the panel.

Kiana Wilson (Photo: Rashika Williams)

Attending a sneak preview, with not even one-fourth the audience as opening night, the spectacle and magic within the actresses’ performance remained intact as Strum looked on as a proficient mother. After the preview performance, she instilled wisdom into the actresses, asking each to deliver their lines on opening night towards new horizons, “Don’t leave anything off the stage.” And so, in the next twenty-four hours, Shange’s majestic poetry, Strum’s realistic direction, and the actresses’ (Theresa, Khenedi, Destini, Shadae, Laniece, Tiera, Bria, and Kiana) tenacity were showcased to a crowd of spectators, many who were unaware of the magnitude of the night’s event.

After the sickening thud, donned in colored cloth wraps, the play transitions into a series of poems that illustrate the contrasts of being an African-American woman. Shadae Graham’s Lady in Pink performance showcases a woman’s urgent sexuality, often dismissed compared to men’s; Kiana Wilson’s Lady in Green performance, one of the emerging standouts, illustrates the innocence of first love of books, into the continuation of men; Khenedi Daniels’ Lady in Orange performance, embodying the annoyance of being a black woman walking down the streets of Harlem.

In each of these characters, their accessories represent a symbolic theme throughout production and African-American history. Laniece’s Lady in Yellow sunflower hair accessory, Tiera’s aqua blue headscarf referencing her performance as Lady in Blue, Kiana’s Lady in Green afro pick earrings (the symbolism of the 1960s, where African-Americans fought for an equal opportunity amongst their white counterparts), and Bria’s Lady in Purple Black Lives Matter hoop earrings (the symbolism for current-day protests focusing on African-Americans angst towards police brutality, America’s prison system and nonchalance people care about the death of black men and women).

As the play begins to reach its third act, the show’s most standout scene that will forever embed audiences’ memory is Destini Fell’s performance as Lady in Red. Lady in Red, previously introduced through her monologue as a battered forgotten woman when experiencing an abortion, returns in the production’s third act. Telling the story of Crystal, a woman with two children, and an abusive co-parent named Willie Beau (a consistent drinker, who fought in the Gulf War), Beau sees Crystal as his and only his. The character goes to Crystal’s apartment and inexplicably alters her life forever. Matched with Fell’s emotionally raw driven performance and Zachary Campbell’s (accompanying musician for the production) powerful instrumental, the scene ends with the imagery of Willie dropping Crystal’s kids from their apartment window. Now, Crystal is left to fend off the world herself, without the two joys of a mother’s life.

Seconds later, the characters each appeared on stage and performed “A Layer on of Hands.”The cast expounded, “I found God in myself and I loved her fiercely.” They then comforted each other, posed as Queens of Their Domain, collectively establishing an unbreakable bond highlighting the choreopoem’s profound message of female companionship and self-love.

Soon after, a standing ovation consumed the theater, with people screaming and rejoicing the actresses. Imani Jenkins, a Mass Communication student and creator of UNITY (an annual Black History Month event held at Five Towns College), tearfully puts the night’s retrospect in three words, “I’m so proud.”

In the forty-five years since For Colored Girls Who Considered Suicide When the Rainbow is Enuf, was released, black women still go through the same dilemmas as depicted in the choreopoem. As Shange’s early inspiration, Malcolm X said in May of 1962, “The most disrespected women in America is the black women,“ rhetoric the cast echoed during promotional interviews.

In the year 2019, alone, African-American women have fought for the rights of their loved ones after they are either shot by police officials or confined to the prison system. Seen through the activism of Eric Garner’s daughter, Emerald Snipes, and Garner’s mother, Gwen Carr, these two women have fought the New York City Police Department for five-years for the imprisonment of the two officers who killed Eric Garner through an illegal chokehold, Daniel Pantaleo and Justin Damico. Only to no avail.

When not fighting the justice system, a black woman could be killed by law enforcement, as seen in the case of Atatiana Jefferson. Jefferson was a 28-year old Texas woman, who was protecting her property and nephew after a neighbor called Fort Worth Police Department for a wellness check after recognizing Jefferson’s door was open one early morning. When she heard someone walking in her backyard, she brandishing a gun (Texas is a gun-carrying state). The police responded by instantly shooting Jefferson, perceiving her as a threat instead of a law-abiding citizen.

When not protecting their loved ones from the dangers of the world, black women are fighting for them in their womb. Earlier this year, Beyonce and Serena Williams, two of the most prolific figures in their respective fields, revealed strikingly similar stories of life-threating complications from their pregnancies. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, black women are three to four times more likely to die from pregnancy-related complications than any other ethnicity.

Malcolm X’s rhetoric from 1962 doesn’t only apply to African-American cisgender women in 2019, but also transgender African-American women, who are fighting for survival. In the last 11 months, 24 transgender people were murdered – 18 of them were black. Often killed by scorned lovers, or hate crime perpetrators, The Human Rights Organization said more transgender people have probably been killed, but haven’t been documented, due to victims being misgendered by local police and media.

Globally, black women are treated the same way, or sometimes worse, than in America. On April 14th 2014, female students from Government Girls Secondary School in Nigeria would have their lives changed drastically. While in class, the local extremist terrorist group, Boko Haram, kidnapped 276 girls for unspeakable horror. Five years later, 112 girls are still missing. Aged from sixteen to eighteen at the time of their kidnapping, these girls could’ve aspired to become a mother, a lifesaving doctor, or the President of a nation. Instead, their stories would never be realized because they’re held at the control of men – the perceived patriarch of their society.

Ntozake Shange’s, For Colored Girls Who Considered Suicide When the Rainbow is Enuf is not just a simple play. It’s a heralding piece to disenfranchised women; black women who want to be seen, who want to be heard. “Telling the real raw stories of black women,” Professor Malisa Ali said, “we don’t get that in textbooks.”

On October 27th, 2018, Ntozake Shange died after being wheelchair bound for a better part of a decade after suffering a series of strokes in 2004. A year and three days later, her light resonated with Five Towns College’s rendition of her tour-de-force choreopoem. Director Lisa Strum, musician Zachary Campbell, and the cast received a standing ovation, with Laniece Lebron saying, “It hit me the hardest when my mom saw me after the show and just started crying. She barely cries and told me she was so proud.” The Saturday night performance boasted a crowd more packed more than opening night, thunderously applauding, with a student giving each actress a sunflower after the performance.

During Sunday’s last performance, the air was blissful and filled with pride over accomplishing a feat that will undoubtedly create a standard for sequential productions for the college. Marking her exit to the cast of blossoming performers, Destini Fell said Lisa Strum imparted one final lesson, “Let the words and the dialect help your movement, don’t worry about the audience.”

The three-day production of For Colored Girls ended, but a lifetime of lessons and friendship will endure. A month after the production’s completion, several cast members (Destini Fell, Bria Walton, Kiana Wilson, and Khenedi Daniels) were nominated for Best Actress at the student-voted “For the Culture Awards.” After securing the award (Destini Fell, Lady in Red) and winning the major award of Best Play/Musical, the success of the production reached its pinnacle point on December 9th when a highly regarded organization invited the cast to perform.

The Kennedy Center American College Theatre Festival, affirms John F. Kennedy’s belief of advocating and preserving American art. The festival showcases colleges from different sections of the country and each of the participating institutions must display a diverse, conversational, and important piece within American theatre. Head of Theatre, Dr. David Krasner, submitted the production as a full piece to the festival, and on December 8th, received the notice that the cast and production of For Colored Who Considered Suicide When the Rainbow is Enough, will be performing at Cape Cod Community College next January, under the northern region (the festival hosts eight different regions). “As a black actress, this is a dream come true,” Tiera Summers said in an Instagram post relating to the announcement.

Destini Fell, Tiera Summers, Bria Walton (Photo: Professor John Blenn)

The experience of this production hits each actress differently, but for Bria Walton, For Colored Girls, marked her last production under the college where she met her teachers, realigned her faith, and met her closely knitted band of “sisters” (The actresses often called each other sisters during, and after the production).

“After high school, I didn’t know what I wanted to do. I ended up at Five Towns in the spring and if I started originally in the fall semester, I would not be in this show. I would not be going to ACF (American College Festival),” said Walton.

“I hope we continue to do stuff that’s exciting, that’s cutting edge, that’s controversial, that has meaning to the actors and the audience,” said Dr. David Krasner.

(Photo: Gillani Peets)

Envisioned as a letter to ongoing depression, For Colored Who Considered Suicide When the Rainbow is Enuf, is a bittersweet journey of the emotional turmoil of being an African-American woman, transcending years later, with the same profound messages as the original. The acclaims are rightfully deserved for each participant of the production (including stage director, costume designer, etc.) as the world is entering a new decade of endless possibilities without its author, Ntozake Shange.

These possibilities are brought to life by Dr. David Krasner, Five Towns College’s Theatre Department, Theresa Coleman, Khenedi Daniels, Destini Fell, Shadae Graham, Laniece Lebron, Tiera Summers, Bria Walton, and Kiana Wilson. And all of the colored girls around the world.